NO OTHER injury in the AFL has such a high recurrence rate.

Alarmingly, half of the players who suffered a posterior cruciate ligament setback in 2017, as per last year's AFL injury survey, had a relapse later in the season.

The list of stars dealing with the problem now or previously includes Richmond's Jack Riewoldt and Tom Lynch, Giant Shane Mumford, Hawthorn's Grant Birchall, Bomber Devon Smith and Collingwood's Daniel Wells.

FULL INJURY LIST Who's ruled out and who's a test?

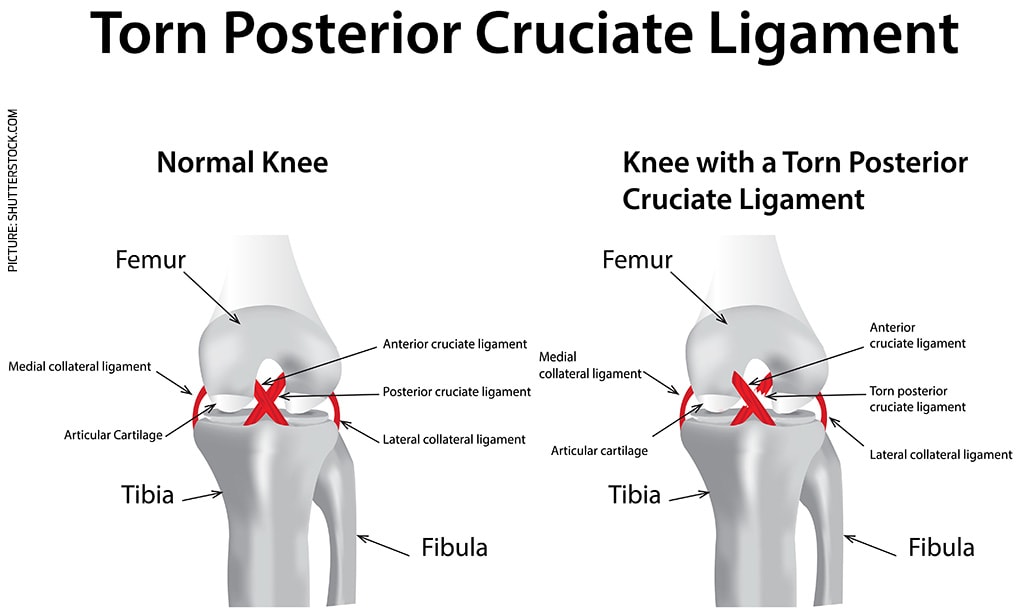

A PCL injury is rarer than a footballer hurting an anterior cruciate ligament, but the rehabilitation program – including whether to undergo surgery or not – is more complicated.

Fit for Footy co-founder Leroy Lobo, who worked at Greater Western Sydney for seven years and consulted for the Swans, has given AFL.com.au an insight into PCL injuries.

How does a PCL injury occur?

There are two more common ways, although the vast majority of them happen when there is contact to the front of the shin, just below the knee, with the knee bent or flexed.

"The PCL injury isn't as common as the ACL, because the PCL is thicker, and also due to the mechanism that has to occur to hurt your PCL," Lobo said.

"You may have players who are tackled to ground, or players in the ruck that take a blow to the top of the shin – below the knee – from colliding with each other in the ruck contest.

"The other way is more of a hyperextension. It's not as common but it can happen."

There are three ascending grades, with the least severe being a Grade One.

Jack Riewoldt in round two with his knee iced up. Picture: AFL Photos

The rule change

The AFL introduced a 10m centre circle for the 2005 season, in response to research that showed about 30 per cent of ruckmen had sustained a PCL injury in a centre-bounce situation.

"It used to be called a ruckman's injury, because they would run from 15m or more apart and jump at each other, and when your shins impact each other with the bent knee, there's a risk of (hurting your) PCL," Lobo said.

"The AFL understood that, so they changed the rule around how far back the ruckmen can run into each other at the centre bounce."

A 2009 study found there were 12.9 PCL injuries per 10,000 player hours and 5.6 ruck injuries per 10,000 centre bounces between 1999 and 2004, which tumbled to 5.9 and 0.9, respectively, post the rule change.

What is the recovery period?

A player typically misses between four to 12 weeks, depending on the individual's knee-related history, the grade of the PCL injury and whether there are other injuries to the knee.

That prognosis also assumes they don't require surgery, and the rehabilitation goes to plan.

"If it was meant to be four weeks, and it blows out to six – that's not the end of the world, so long as the player's making progress overall," Lobo said.

"But if it's meant to be four to six weeks, and at four weeks, they've still got swelling in their knee and they can't progress as per their rehab plan, then you're probably considering surgery."

The recovery time from PCL surgery varies from about six to nine months.

Essendon is predicting a six-month stint out for former Giant-turned-Bomber Smith, who has undergone dual PCL and trochlear operations.

In another example, Collingwood's Wells has elected not to have surgery to give himself a chance of returning this season.

Devon Smith leaves the field in round six after the Bombers' loss to Collingwood. Picture: AFL Photos

The rehabilitation process

The first week of "conservative management" (no surgery) is spent reducing the swelling in the injured knee, before the emphasis turns to basic strength work in the gym.

An interesting aspect of the initial recovery phase is the potential for a change in diet to avoid the player putting on weight.

"If you're out for a while and not training, straightaway the first week the player is changing their diet, because if you're eating like you're playing games … then you're going to put on weight," Lobo said.

"If you're out for a short period, then you're not really (changing your diet), but if you're out for six-to-eight weeks and not running for three weeks of that, then you do.

"What's the last thing your knee wants when you come back? Carrying more weight."

The athlete will transition to running on an AlterG anti-gravity treadmill once knee strength reaches a certain level, because they can't run on the ground at this stage of the process.

There will also be pool and bike work to ensure the player doesn't lose too much conditioning.

Find Trends on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts and Spotify

Eventually, once the injured knee's strength has reached an appropriate level, the on-ground running begins.

Strength remains a key element of this phase and they will do more strength work in the gym, and the running volume then intensity will increase, as well as them starting to change direction.

The next step is getting involved in low-level skills and match-specific training drills.

"You must build up your strength, then maintain that strength as you build up your running loads," Lobo said.

"If the strength drops, it's a pretty good sign your knee is going to go backwards pretty quickly."

Managing a PCL deficiency in-season

It is unknown how many AFL footballers play through a PCL deficiency, but Lobo predicted there would be many we weren't aware of.

Managing this problem while playing is a difficult process because of match variables, such as further knocks to the knee, having to play higher game time, and individual running loads.

You also have to factor in a player's weight and size, as well as their playing style, all of which can increase the loads on the PCL-injured knee.

"You can have all sorts of things happen that are out of your control in a game, then the player must back them up within six or seven days, which sometimes doesn't happen with a PCL-deficient knee," Lobo said.

"At some point, maybe they don't train with the main group during the week, and the coach might eventually say, 'You're missing a lot of training; you need to do some training during the week'.

"There is a fine balance between managing the player's knee during the week between games, and the player missing too much training."

What can go wrong?

There is constant dialogue between the injured player and the medical team, much of it based on whether there is any ongoing pain and with a focus on the swelling or lack thereof.

Ideally, the athlete will progress without pain or an issue with swelling, both of which proved a problem for Hawthorn's Grant Birchall each time he reached the latter stages of his recovery.

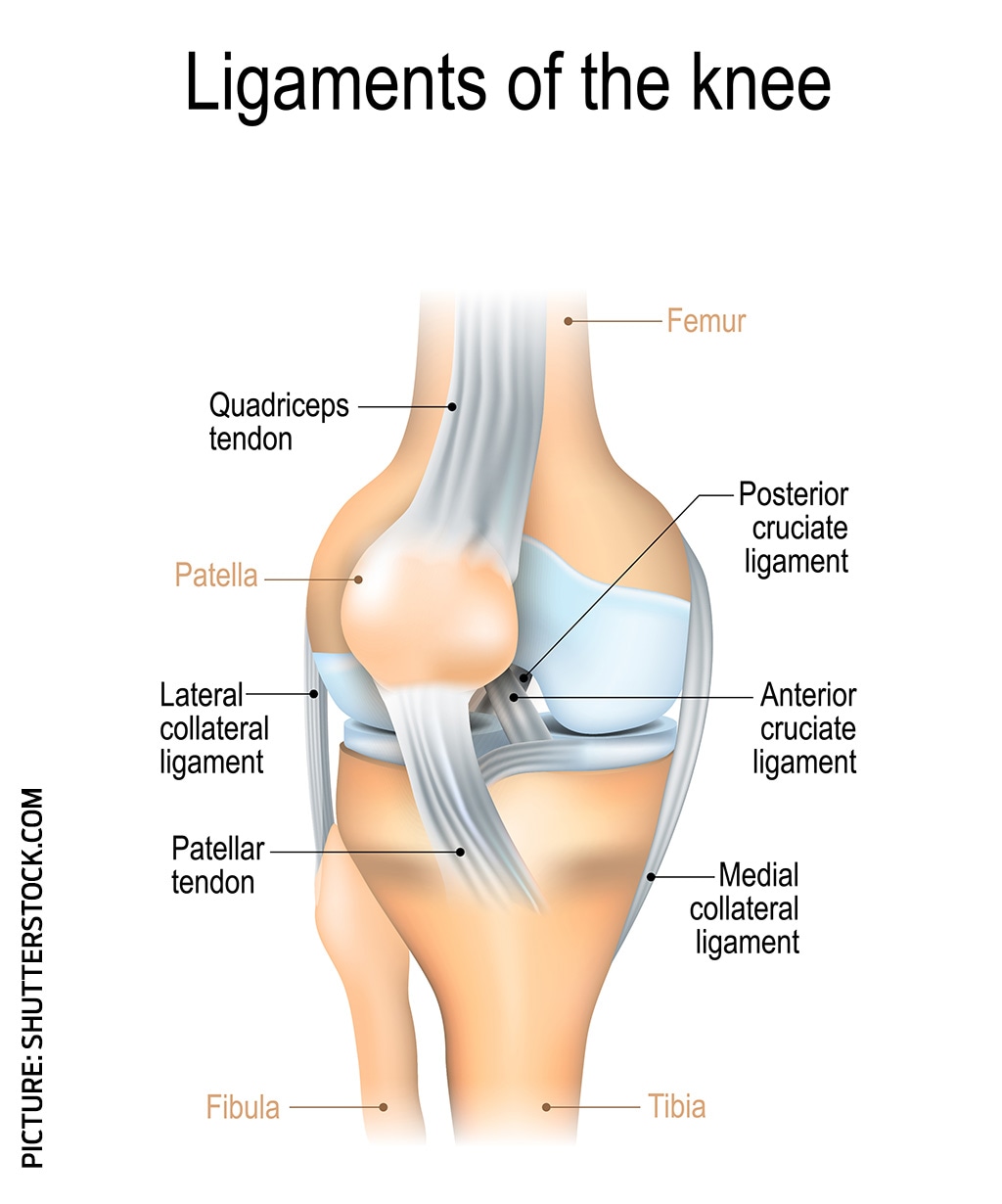

"The decision-making is, 'Can we settle this knee down, build up and maintain this player's strength in all the key muscles, especially the quads, glutes, hamstrings and calves?'," Lobo said.

" 'Can we build up the strength, then expose them to training loads – running, jumping, cutting, match-play? How is the knee responding?'.

"If it responds favourably, which a lot of them do, they just conservatively manage them without surgery, and prepare them for games.

"If it doesn't work, they consider surgery, but that usually ends a player's season."

To have surgery or not?

The ACL injury is far more common than the PCL equivalent, and the surgery and management is better understood, according to Lobo.

Dr Peter Larkins told News Corp in 2018 there were about 1800 ACL operations in the previous two years at the Epworth hospital, compared to 14 of the PCL variety.

"There's a lot of discussion around whether it's worth doing or not," Lobo said of PCL surgery.

"Surgery is more commonly performed if multiple structures in the knee are injured, such as the PCL and other ligaments.

"One reason they don't commonly perform the surgery is that when they studied athletes' knees in the mid-term, so the next five to 10 years, they found there was no significant difference in the outcome if you operate on the PCL or manage the injury without surgery.

"The first part of the decision-making process for the player and the surgeon is, 'What's the benefit? If there's not much of a difference, why am I doing it?'."

FEELING THE PAIN The full 2019 injury ladder

Essendon's Smith was always going to need surgery at some point to repair his PCL deficiency, but he was able to function OK without it.

It’s only now he requires an operation on his trochlear, underneath the kneecap, that the timing made sense to also have the PCL surgery done.

"The questions to the player are, 'Can you play and can you perform your role? Does it impact you?'. If it's 'Yes' to the first two and 'No' to the last one, then you can keep going," Lobo said.

"But if it starts to impact your knee's function, if it starts to impact your ability to train and play games, and if there is wearing to the surfaces in your knee, then surgery becomes a consideration."

Find AFL Exchange on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts and Spotify.